Iowa is speckled with tide pools. Not the coastal kind, obviously, but grassy puddles and droplets of remnant prairie. They lay sprinkled across the tilled and tiled land like low tide catchments of saltwater along a rocky coast.

These pools are isolated vestiges of the Sea of Grass that once flowed over the state. They’re all that’s left, the last 0.1% yet to be drained away through moldboard furrows like city rain falling through curbside sewer grates.

How does that kind of fragmentation impact the plants and animals that need prairie to survive?

Imagine a coastal tide pool. Low tide leaves a grab-bag of sea creatures scrambling for water and hunkering down in the pool’s catchment to wait ‘til the ocean comes back and expands these refugees’ world again. Business as usual. Happens every 12 hours and 25 minutes.

But what if the ocean doesn’t come back? What if the moon-drawn tides disappear and leave these oddball collections of castaway organisms to their own devices for a decade or a century? That’s the scenario our prairies are in.

Life in that kind of fishbowl would affect different organisms in different ways. Some would thrive, some would flounder (no pun intended), yet others still might not be altogether trapped.

Starfish and crab, for example, could probably shimmy and scuttle across the rocks and sand to nearby pools. They’d venture out, spurred on by an urge coded in their genes to risk brittling in the sun or becoming a gull’s lunch to try their luck in a new pool of unknowns.

The same could be said about migratory grassland creatures. Dickcissels and monarch butterflies are capable of flitting about in search of greener pastures. There’s no guarantee the prairie puddles they find will fit their particular habitat and resource needs, but they take their chances with the nest-hunting mesopredators and flowerbed neonicotinoids all the same. Roaming is all they know.

While the crab, starfish, dickcissels, and monarchs search, the pool-bound organisms sit and wait for high tide. Like barnacles and anemones, the prairie’s blazing stars and racerunners linger, stuck in their shrunken worlds.

Will they find a mate? Will they be overwhelmed by more aggressive organisms? Is there anything to eat?

They watch for their respective waves of saltwater or grass to return while dealing with whatever luck of the draw has left them. The sea creatures have dealt with this, are adapted to the routine of momentary isolation, are sure the water will come back. But the grassland-dependent organisms are left holed up, hoping against hope that the prairie, like the sea, could be drawn by the moon.

Loess Hills ridges themselves appear a bit like they’re being pulled to the heavens. Looking east from atop Badger Ridge, for example, a bare, black soil valley is rung near-entire with vertical loess slopes thrusting towards the sky, draped in golden velveteen prairie. The linear brass-colored ridges look like fingers spreading from a palm-less hand, or some disparate, frozen, amber waves heaving moonward from an opaque sea.

Each ridge of these ridges is its own prairie tide pool that’s been isolated for nearly 200 years. The distance between them might not seem significant to a dickcissel or monarch, but what about the race runner or blazing star? To them, the divide between ridges is as impassable a stretch as dry sand to a minnow. The prairie-bound organisms can’t cross that gap without being exposed as prey or having their seed tilled under.

They need a reconnection. They need a reunion. They need the tide to return.

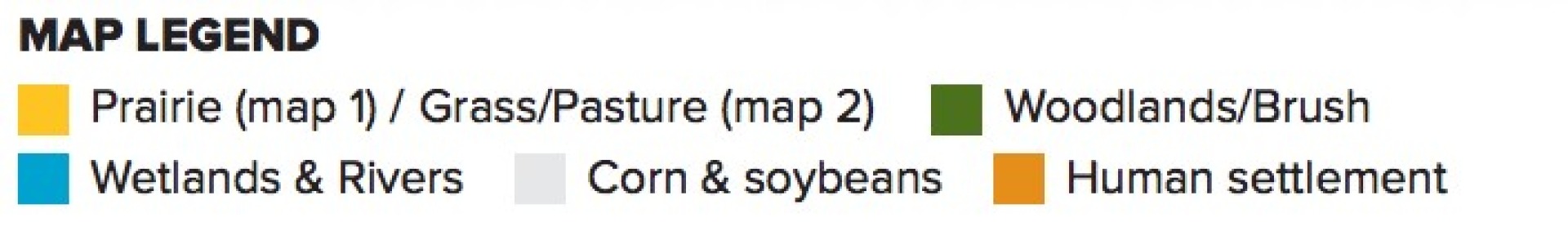

Pool to pool, puddle to puddle, reconnecting these stubborn droplets of prairie is one of the most important things the Pottawattamie Conservation Natural Areas Management department does. The moon might not be able to raise the tide of grass, but our guiding principles pull our team to the cause, reuniting remnant prairies through restoration plantings and stewardship, improving the land’s resilience and diversity.

The valley east of Badger, the ‘missing palm’ or ‘opaque sea’, is no longer. It’s been replanted with 110 different species of native forbs (wildflowers), sedges, and grasses. Now in its second growing season, it’s starting to look like prairie again. More importantly, it has reconnected the remnant prairie ridges that encircle it.