These popular topics are heating up. Explore today's most viewed pages.

These hills are part of the greater Loess Hills landform which took shape approximately 12,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age. Huge quantities of powdery quartz deposits known as “loess” were dumped into the Missouri River Valley as the glaciers retreated. Westerly winds blew this sediment up and out of the valley into a line of giant dunes that have subsequently been eroded into the ridge-topped hills and bluffs we see today.

The first humans in this area were Native Americans. These early visitors were likely migratory hunters following mammoths and ice age bison along the receding edge of the glaciers. Over time different groups settled in the Hills. Some maintained their migratory hunting lifestyle, others relied more upon agriculture and trade, and most probably utilized a mix of the two. Regardless of the specific cultures, one thing was constant: frequent prescribed fire.

Native peoples intentionally set fire to these hills and the wider region for thousands of years. The practice drove and maintained the landscape as a hugely diverse patchwork of grassland ecosystems. The resilience and health of the landscape became dependent upon the indigenous people’s cultural fire practices. Burning the prairie recycled nutrients, kept woody plants at bay, and increased herbaceous plants’ palatability. From the ashes arose lush vegetation which attracted and sustained large herbivores. Indigenous people took advantage of this relationship between fire and grazers; hunting bison, elk, and other animals in the lush grasslands that were a direct result of their own torches.

As time went on new people came into the area. They brought with them novel diseases, plants, and animals as well as an entirely different perspective of the land. These people did not consider themselves to be part of their surroundings, but masters of it. They saw land as a utility, a means to an end, and treated it as such. These people flooded into the region, displaced the native peoples and herbivores, divided the land into parcels, built fences, plowed up the valleys, and overgrazed what was left of the prairie with domestic cattle. This fragmentation and resource extraction had become the driving ecological drivers of the Loess Hills.

The land that is now fondly known as Mt. Crescent, though, took a unique turn in the 1950s and 1960s. At that time a small group of skiing enthusiasts from Omaha purchased the property with plans to install the infrastructure needed to make themselves their own personal ski hill.

They couldn’t keep it to themselves, though. The local community wanted to ski too. The owners eventually began allowing public visitors to utilize the slopes.

In 1974 the property was sold to Russ Lindeman as a personal country retreat. But again, the community wanted in. They loved that piece of land. The overwhelming interest in the ski hill convinced the Lindeman family to start a new business: Mt. Crescent Ski Area.

Meanwhile, the changes in the land’s biological communities were nearing a tipping point. Excluded from fire and native herbivores, the weakened prairie couldn’t keep out aggressive woody and non-native herbaceous plant species. One exception remained, though—the ski slopes themselves. While mowing is not the same as fire or grazing, the act did maintain the runs as grassland and much of the prairie persisted.

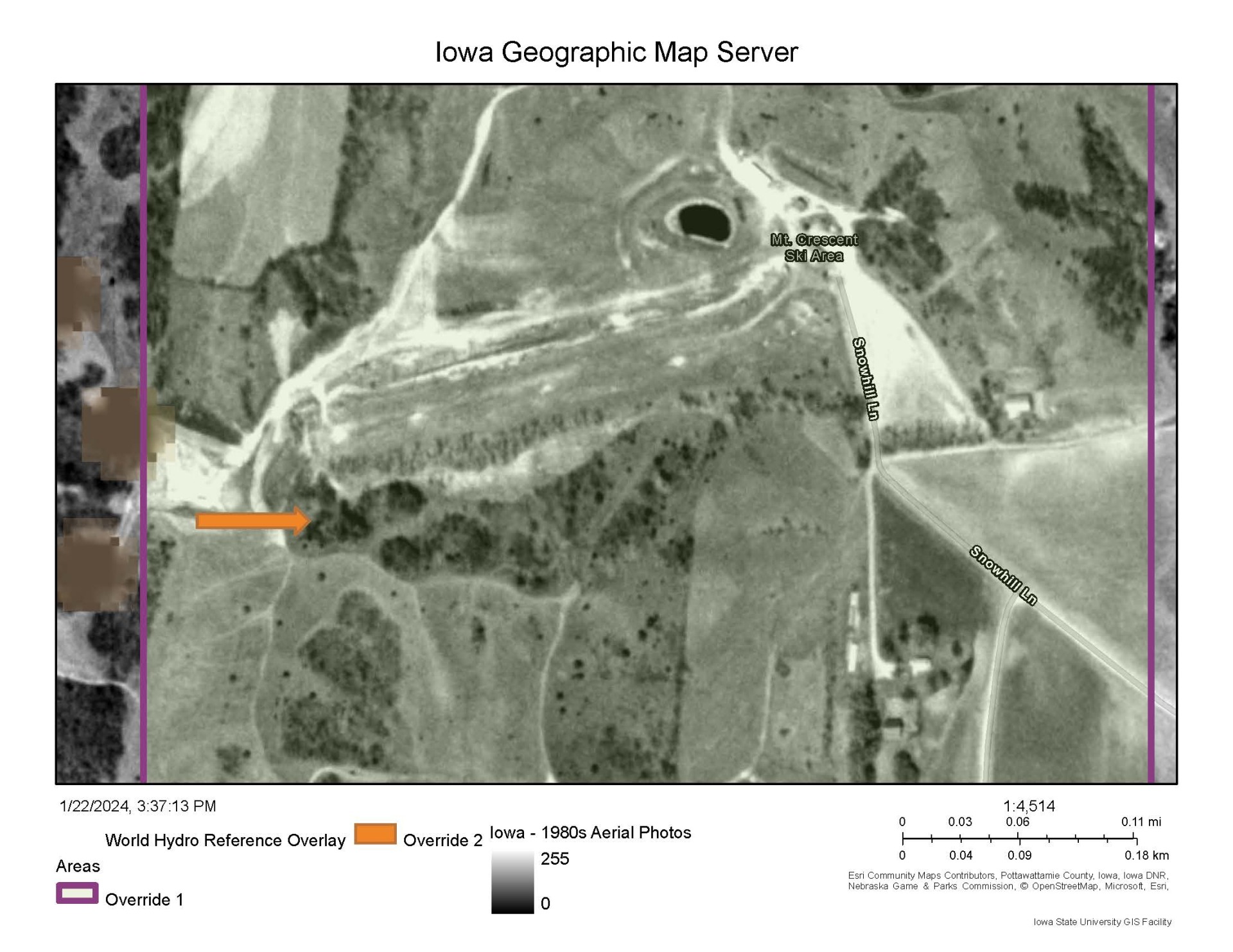

The 1980’s and 1990’s saw major expansion and upgrades to the skiing operation: fairly extensive dirt work including grading, trenching of pipes and electrical lines, and the installation of a second chair lift. The reinvestment of the operation was an economic benefit to the business and allowed for larger groups to enjoy the hill.

However, the upgrades were ecologically costly. Bulldozers and excavators reshaped entire ridges and slopes, destroying several acres of irreplaceable remnant prairie. Remarkably, some areas of prairie did recover, a testament to the prairie’s inherent resilience, though we’ll never quite know what all was lost.

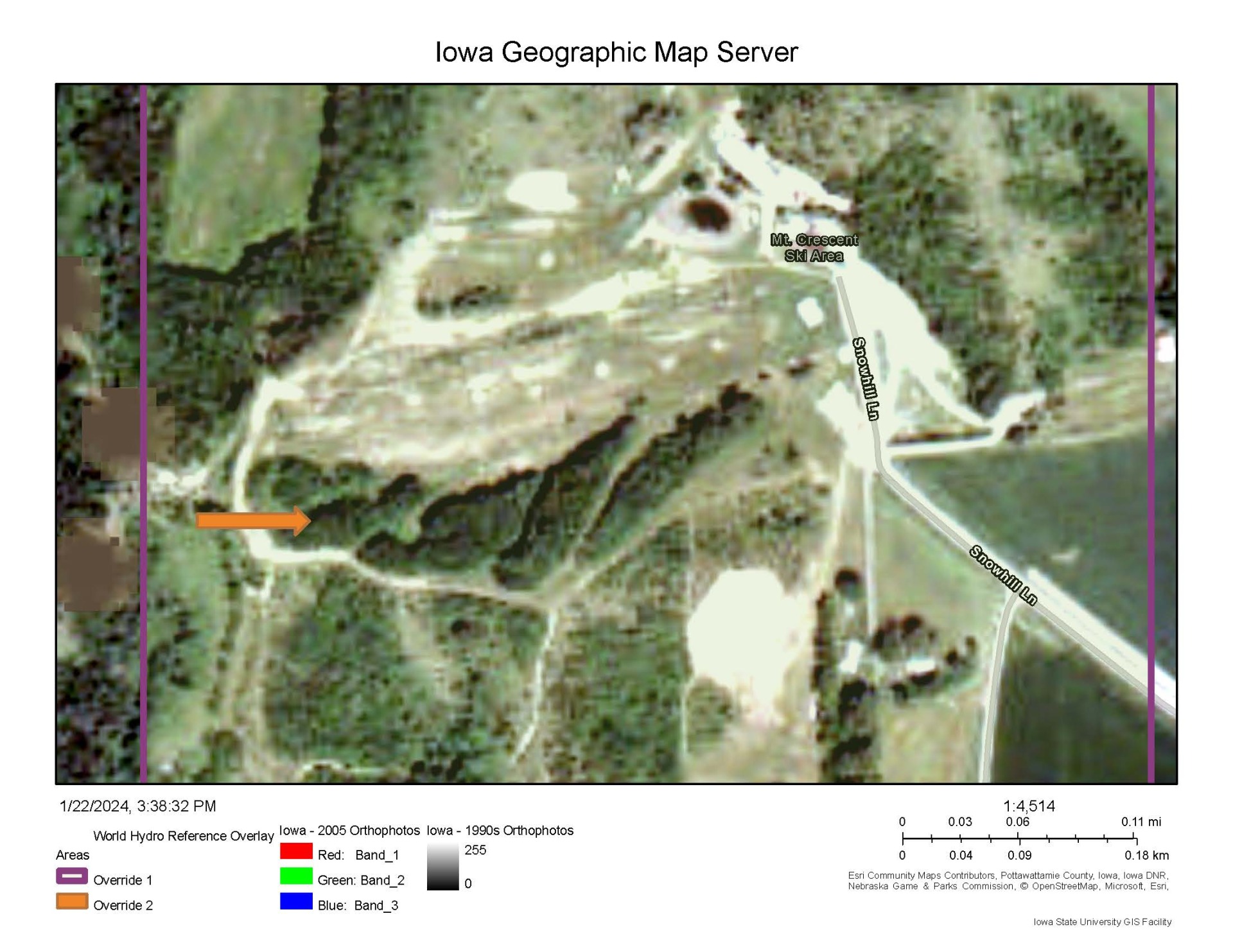

While the prairie was being dozed and reshaped, it was also in a struggle for sunlight. The 80’s and 90’s are especially remarkable in the advance of eastern red cedar. What was wide-open grasslands only a couple decades earlier were now becoming crowded with thickets of the invading conifers. Without fire and grazing the cedars took hold and shaded out much of what was left of the prairie.

The ski hill operation changed hands in 2011. The Lindeman’s sold the property to a different operator. Skiing remained the main attraction, but other recreation activities were added including a BMX course, a zipline, an obstacle course, and paintball, all requiring different levels of disturbance to the land.

In 2022 Pottawattamie Conservation purchased the 102-acre property. Public interest was high. There were concerns that the skiing operations would end. However, Pottawattamie Conservation saw this as an opportunity to protect and improve this unique outdoor recreation the land provides which has proven again and again to be so valuable to our community.

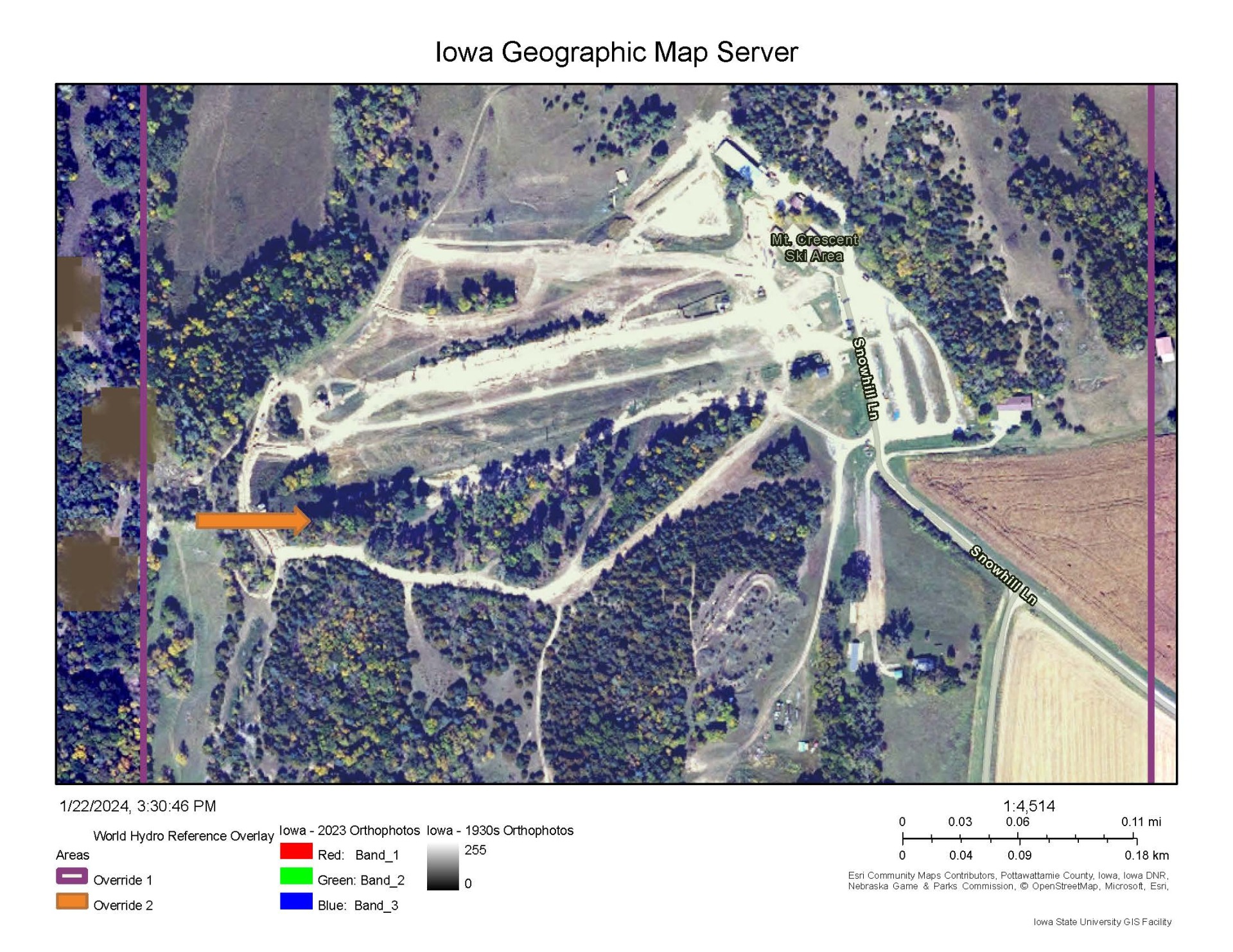

Since being acquired by Pottawattamie Conservation our Natural Areas Management department has begun restoring health to the land. The largest and most obvious project we’ve conducted at the ski hill is the removal of brush and thinning of trees on the north-facing slope just south of the double lift.

Like every other area of the ski hill property, this area has been heavily encroached upon by woody species that have shaded out what was once prairie and savanna. Brush removal and tree thinning allow more sunlight to reach the ground and herbaceous plants to flourish. Restoring this vegetation improves soil health, reduces erosion, improves water infiltration and provides essential resources for wildlife. It also allows more access to skiable acres.

Projects like these will continue in the future as the Natural Areas Management team continues its work to restore our native ecological systems.

Special thanks to Dave Yrkoski for providing important background information and context on the history of Mt. Crescent for this post.

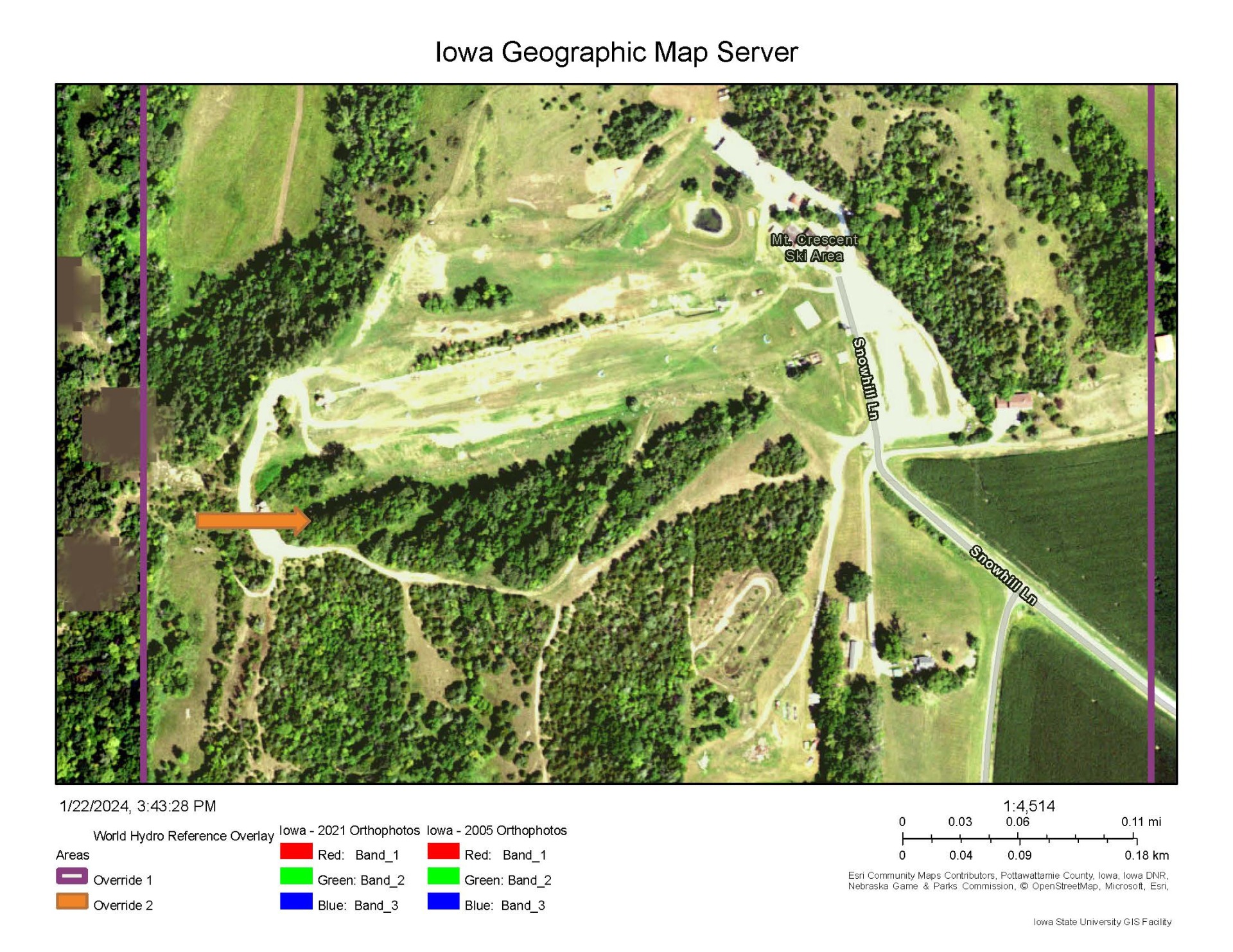

Images courtesy of Pottawattamie County GIS.

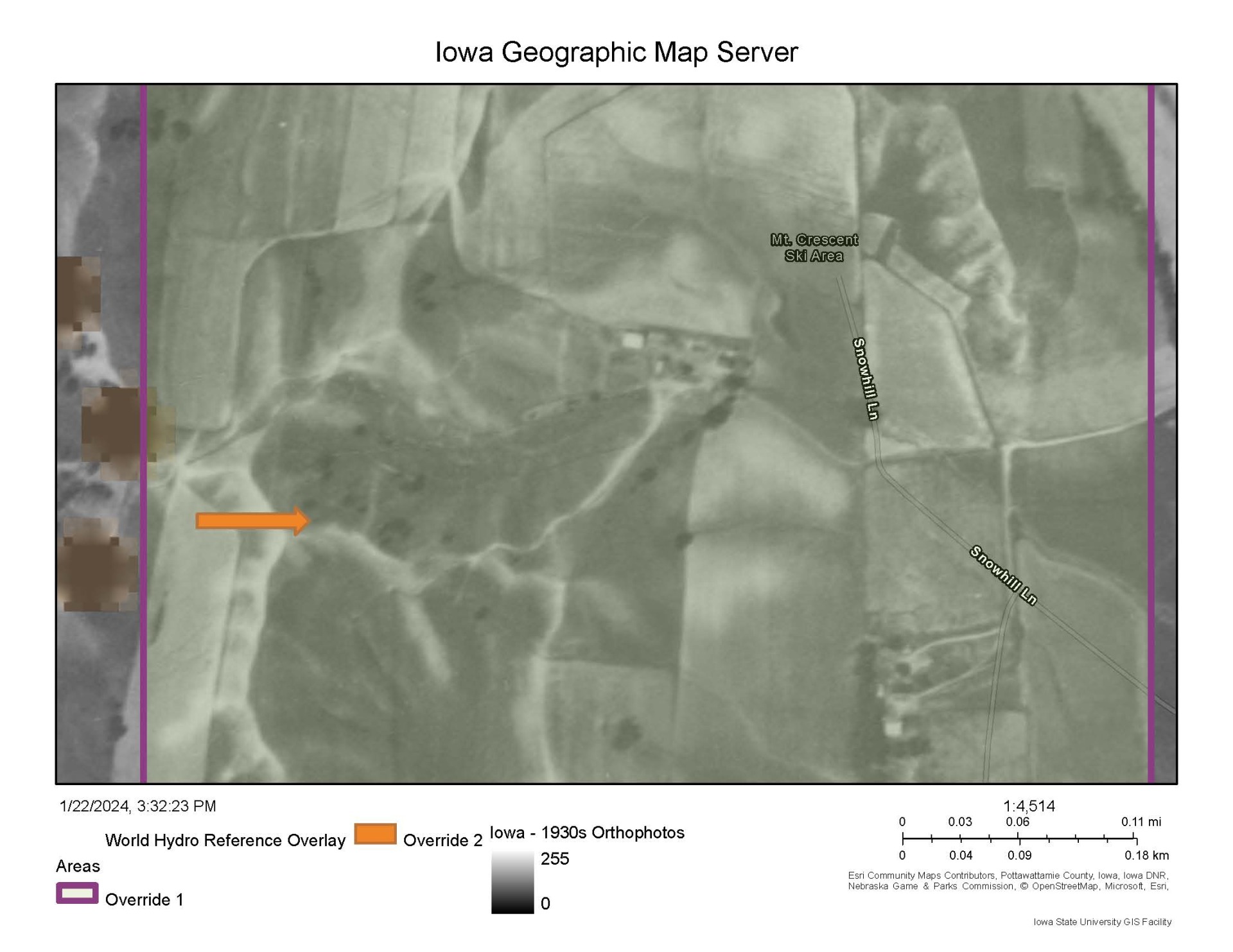

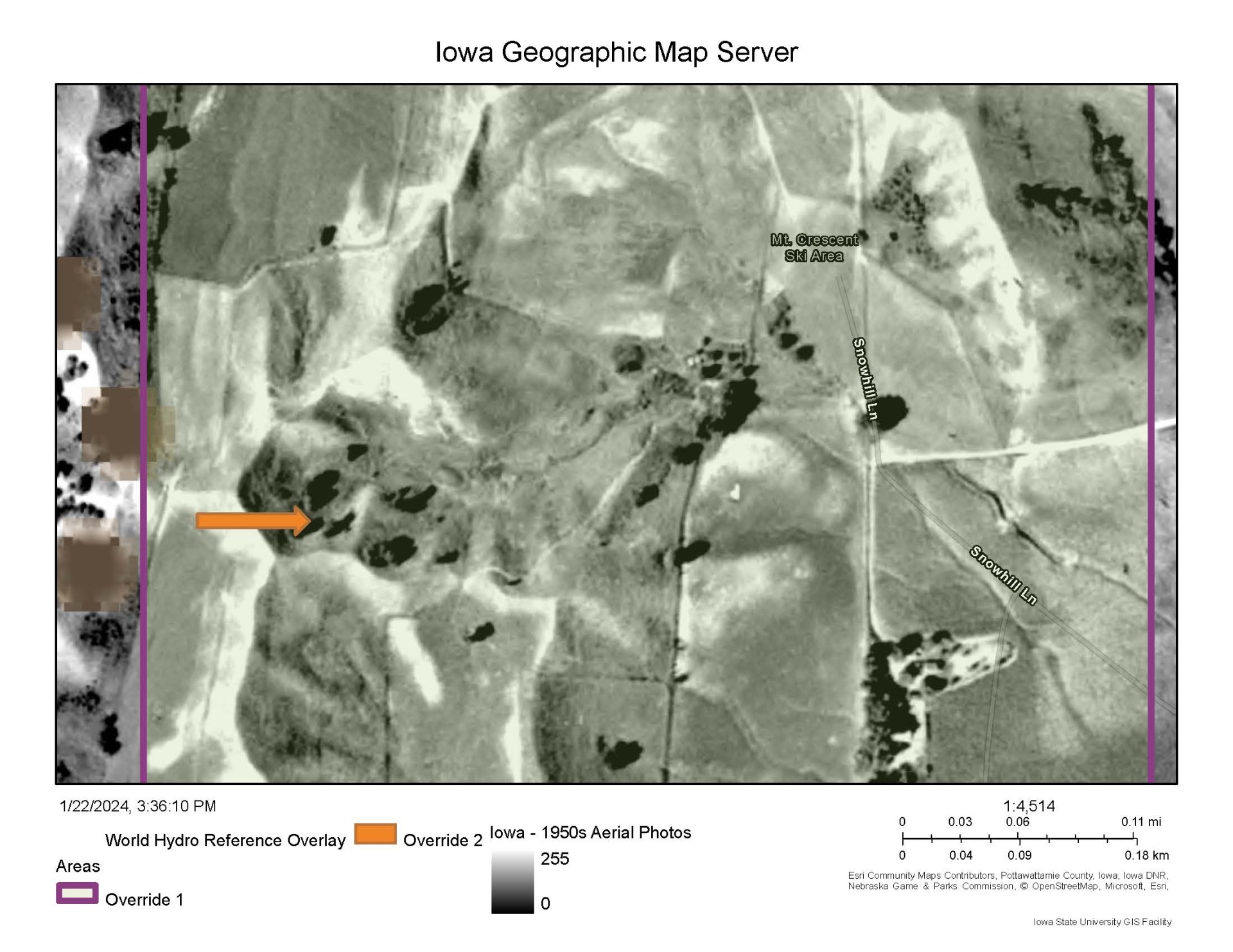

1930s, 1950s – Nearly entire prairie with some open grown oaks.

1980s – Major increase in woody encroachment, extensive dirt work.

2000s – Extensive woody encroachment, more dirt work.

2021 – Closed canopy, also can serve as a “before” thinning project.

2023 – Shows some of the thinning work. Note more sunshine getting to the ground. Note the area is not healed but has been set onto a healthier trajectory.